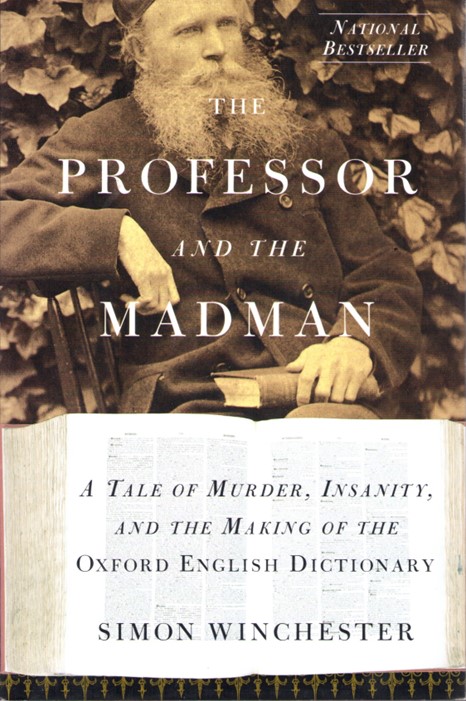

DEFINE “ARCHGRAMMACIAN” OR DO FIVE-DOLLAR WORDS DEFY, STYMY, OR INSPIRE ME? (“PAGE 85 SUCKS!”)

A POSTMORTEM ON ONE PAGE IN

THE PROFESSOR AND THE MADMAN:

A TALE OF MURDER, INSANITY, AND THE MAKING OF THE OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY

by Simon Winchester

Written by Francis Baumli, Ph.D.

New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1998.

At least a dozen people have contacted me over the last few years, inquiring about words they did not understand in this book by Simon Winchester. If I did not find their queries irritating, I sometimes did find them rather unnecessary, because all the “big” words that occur in this book, except for eight words or word-phrases, are in the Oxford English Dictionary and people could have (and should have) looked them up. As for the eight words or word-phrases they could not so easily look up, I have now defined them and they are in my own publication, “Oxford English Dictionary Supplement: Word Candidates, Corrections,” which is located in this same section of Baumli’s Mirror. My point being: the book’s words are not as daunting as many people found them to be, and now they should no longer be daunting at all since I have filled in the OED’s missing gaps.

However, I do concede that looking up this many words is a tiresome task for a person whose real desire is to just keep reading. Also, I think there were times when Simon Winchester was purposefully trying to be difficult, cleverly (though amateurishly) strutting his menagerie of exotic words, and also taking some degree of private pleasure in the thought that he was causing readerly conundrums.

“Page 85 sucks!” That is exactly what she said, and I was most surprised to hear these words coming from a woman of such scholarly stature. Fernanda is a world-renowned philologist. She was born in Portugal, lives in England, and her command of languages is so impressive as to intimidate. She is thoroughly fluent and at ease with Greek, Latin, every Romance language, Russian, all the Germanic languages including English, several of the Scandinavian languages, and a smattering of others spread about the world. Yet this erudite woman was calling me for help, and from her cultured mouth emanated the declamation: “Page 85 sucks!”

She already knew I had read the book, and she wanted to know if I had had to look up any of the words on that page. I admitted that I had had to look up one: “Rhinegraves.” I remembered encountering this word in Molière’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, but too often it seems I have to, again and again, look up definitions for articles of clothing, no matter how many times I have looked them up before. As for the other words on this page? I did look many of them up, although not because I had to. I was checking to see if they are in the Oxford English Dictionary, since this is one of the scholarly tasks my vocation dictates: locating words that are not already in the OED. I would not have been surprised to discover that Fernanda had encountered difficulty with a couple of the words on this page, but to have found many of them impossible? I truly wondered (and since she is several years older than me—still wonder) if somehow she is “slipping,” maybe getting geriatric, senile, succumbing to Alzheimer’s.

But it is, I concede, a difficult (even cluttered) page. Simon Winchester wrote it this way to illustrate his subject—that the learned men of earlier centuries aspired to using “big” words such as these, and considered themselves quite successful, when they managed to use as many such words as possible.

So … since many people have called me about this page, I here, attempting to administer a modicum of proactive beneficence, translate those big words on the page in question. (And I realize that perhaps I am admitting the magnitude of this difficulty more readily than I had thought the page deserves, given that I, rather unwittingly, just now used the word “translate” rather than the word “define.”)

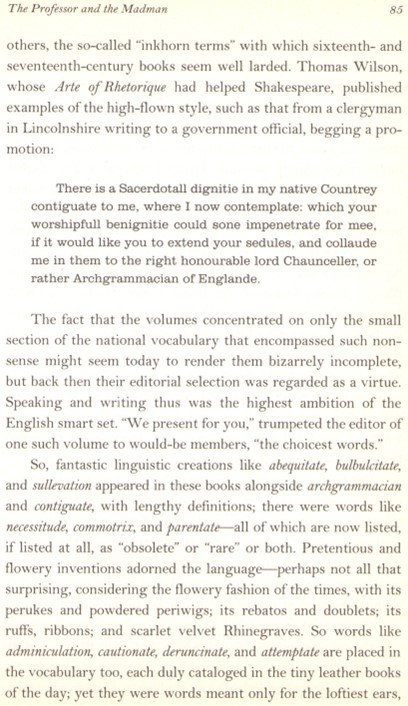

To facilitate this task of translating, i.e., defining, all those difficult words on page 85, I here reproduce that page exactly as it appears in the book:

So now I can proceed to give a definition for all those words on this page which I believe might cause difficulty, with special attention given to the paragraph written by that wordy and aspiring clergyman, trusting that if I do not realize certain of its words need explaining, then an attentive reader can nevertheless discern their meaning from the context of the letter.

Thus I begin what I fear is scarcely a trivial task:(words before the letter)

“inkhorn terms” (also known as “inkhorn words”): words intended to sound pedantic, flowery, or ostentatious—what some people, in the vernacular of today, call “five-dollar words”

(the letter):

“Sacerdotall”: clergical, churchly, or (especially) priestly

“dignitie”: a vocational position (probably religious), usually carrying the implication that it is a high position, or at least a higher position than the one held by the person who is referring to it or aspiring to it

“contiguate”: contiguous to, or nearby [the implication here is that the writer desires this position because it is in his native country which, although close by, he does not now reside in]

“contemplate”: he is considering this position with avid interest, i.e., this is his polite way of stating that he desires or covets it

“worshipfull”: the word “worshipful” has many definitions already in the OED; here it indicates an expression of respect for someone who is venerable, is held in high esteem, or evinces obvious dignity

“benignitie”: kindness, i.e., it is here acknowledged that the person being addressed has a benevolence which could be exercised as beneficence

“sone”: soon

“impenetrate”: importune; request with earnestness or authority

“mee”: me

“like you”: please you

“sedules”: written petitions or requests

“collaude”: extol or praise

“Archgrammacian”: supreme standard and steward of all that is decorous, mete, and right

[So here then, for the reader’s ease, I write out this letter made over into a more modern English. Written out in its entirety, we readily espy that it is an ambitious, if somewhat obsequious, request for help in getting a clergical position. Here is how it would read in the present-day idiom. I number the lines, attempting, as best I can, to follow their order in the original letter.]:- There is a pastorship position in my native country,

- which borders on the country I now live in, and I would very much like to attain that position; doing so would be much more successful were you

- to quickly intervene and thereby bestow your honorable and venerable kindness so as to request this position for me

- if indeed it would please you to extend a letter of recommendation and extol what merits

- I have to England’s right honorable Lord Chancellor, i.e., to he who is the supreme standard and steward of all that is decorous, mete, and right.

[The lines, in my rendering, do not quite “break” as they do in the original. Also, it bears mention that this petitioner’s prose, though flowery, has not one bit of grace or even a sense of “style.” Therefore my rendering of it would be inaccurate were I to interfuse more fluidity than it originally had.]

(words after the letter):

[In Winchester’s subsequent prose on this page, other difficult words lurk coyly (or garishly?), and I here address them, each in turn.]:“abequitate”: to ride away from—applied to a single mounted person, or more likely to a cavalry as it leaves camp or retreats from a battlefield

“bulbulcitate”: the tendency of a bulbous-shaped organ or organism (plant or animal) to proliferate, impinge, or invade—through multiplication or enlargement, as in the root system of a peony flower bush or the ginger plant, or the swollen lymph nodes (buboes) in a patient infected with bubonic plague. Rare as the word was back then, its metaphorical usage was even more rare, when it referred to encapsulated ideas, theses, or feelings burgeoning to spawn more of such

“sullevation”: also “sollevation”: insurrection or rebellion

“archgrammacian”: supreme standard and steward of all that is decorous, mete, and right

“contiguate”: contiguous to, or nearby

“necessitude”: necessity

“commotrix”: a maid to a mistress who attends to her intimate needs such as dressing, undressing, and hygiene

“parentate”: to organize and attend funeral rites for one’s parents, other close relatives, or to perform these duties for someone who is not a relative and yet do so with a sense of devotion such as one would extend toward one’s relatives

“perukes”: a peruke is an ornate or elaborate wig, worn by European men in the 17th and 18th centuries; a periwig

“periwig”: (same definition as above) [Simon Winchester is being self-indulgent and perhaps unwittingly transparent in his attempt at being clever, thus listing two words as separate when actually they are synonyms.]

“rebatos”: stiff, high, flaring collars worn by both men and women in early 17th-century Europe

“doublets”: close-fitting jackets, with or without sleeves, worn by European men from the 15th through 17th centuries (often posing a problem for men who were portly or obese)

“ruffs”: a ruff is a stiffly-starched circular collar that is pleated or frilled; made of muslin, lace, or other fine or even exotic fabrics; worn by European men and women in the 16th and 17th centuries. A ruff was almost de rigueur for portraits during this time

“Rhinegraves”: loose, wide breeches with legs resembling skirts that fall either to the knees or just above the knees but are gathered tightly at the waistband; also known as “petticoat breeches”

“adminiculation”: to give direct material or moral support to; substantiate or corroborate with written sources

“cautionate”: to caution or warn another, or to apply precautions for oneself

“deruncinate”: to cut or plane off that which is superfluous or unwanted, often used in carpentry when planing; also applied metaphorically as when editing prose, a speech, or simplifying laws and codes

“attemptate”: to attempt

A few other difficult words are scattered throughout this book, but they can either be found in the OED, or in my own supplement to the OED herein published in Baumli’s Mirror. If you encounter further problems, avail yourself of these resources. If that effort fails, then you probably need to go back to primary school.

These words: rare or obsolete, obscure or antiquated, Latinate laden or generously Grecian, are certainly remote, understandably difficult for the average reader, and they stood in dire need of Winchester’s own defining hand. Yet they are, in their rarity, if corroded by time and obscurity, quick to yield a sheen when examined and fondled. So if encountering these words first warranted a frustrating, even daunting, search for definitions, then I suggest you loosen yourself from this sense of travail and welcome an awareness that here you were presented with a pleasant opportunity for appreciating the etymological, philological, and lexicographical complexity, even majesty, of words which, if they initially eluded and then even posed seemingly colossal demands, soon went on to entice, next seduce, and then bestow cerebral pleasures so rich and bounteous as to eclipse all stern prejudices about their supposed difficulty as they thence proceeded to present themselves via the reification of a most comely garb that was graced with more than a facade of generosity in the self-subsumed and self-assured steadfastness of their amiable definientia, readily evincing a presence so promisingly material as to banish any reservations about such scarcely retrograde emanations of semantical ordering, instead inviting us to accept them as having a translucid, quasi-corporeal interior, with a mentation so embodied as to allow us to forge with these words a kind of supratentorial thermionic relationship. We realize that, amongst words such as these, there is a dynamic interplay between the language of yore and our current grammatical clamorings, between archaic morphemics and the fertile laborings of verbal and prosaic discourse, all of which involves an almost brutishly mechanical corruscation along with a sometimes ethereal fulguration, resulting in a semiotic transubstantiation that, if occasionally confusing, is nevertheless (and inevitably) quite liberating because it at times allows and at other times actually procreates new ways of thinking and new inceptions of cultural flowering. Thus our language, if it occasionally decays in ways that dismay us, also progresses along avenues that liberate us. These liberating forays become practices that we absorb. Eventually, with these new habits of language, we achieve a relaxed and comfortable familiarity. In short, it all becomes part of our self-identity.

Thus the mutual seduction, which, though done beneath the cloak of pedantry, scholarship, and cellitic immersion, nevertheless reveals how this cloak, or mantle, of scholarly seclusion can be looked upon as a sacred robe—the aesthetized tapestry which veils the portal to our private harem. And what harem can be more voluptuous, sensual, and thoroughly erotic than one populated by words which, when they shed their coy, albeit bejeweled, ornateness and, with a heterodoxical protoplasm of undeniably incipient material form, nakedly embrace our eager and erudite desires as they present themselves before us—actually, here with us—for no purpose other than to be orthographically situated so as to satiate the persistently (albeit chaste) tumescent, deasceticized orbit of our persistently praetervirginal, devotedly nonrefractory, assiduously studious tryst with the penultimate pleasures of this mutually mirroring literary synechism?

Surely you now understand, i.e., you not only apprehend, you also comprehend, this mini-cosmology in which an aroused morphology of hypervirtual (now become thoroughly hylomorphic), centripetal (and scarcely pleonastic) societal dialogue should inspire us rather than irritate or intimidate us.

In short, if page 85 actually does what my friend Fernanda said it does, then it thereby also demonstrates how the intimate instantiation of a plenitude can so unrelentingly entice, arouse, and eagerly consummate.

So when prose is thus so unyieldingly quodammodotative, what is there to complain about?

However, if you must complain, then do so in the patrician mode. Write an article (not an essay) entitled, “The Essay ‘Page 85 Sucks!’ Sucks!” and bring this lengthy dunandunation to an end by making the measured judgement that Winchester’s exercise displayed too much preening pride as he clumsily gilded his already-wilted lily.

My own foray, however, was fun and challenging, creative and evocative, both inspiring and instructive, then quickly (and mercifully) brought to a close.

If you try this kind of exercise yourself, writing an essay rather than a definitive (even stern) article, hoping perhaps to achieve tertiary elegance, be assured that failure awaits you. Yours will be a cheap redundancy. Dallying with this kind of pleasure is, the first time, a cautious, and somewhat clumsy, tentative introitus. The second time it is lubricious ecstasy. A third time would only chafe.(Written: 4-27-2014 to 4-28-2014)

(Posted: 9-5-2015)